| The Politics of [Re]clamation de R. Amy Elman |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

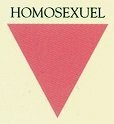

It is incongruous that those pursuing [Gay] liberation can reflect upon the past and insist, as Robert Weltsch could not, that any Nazi symbol can be utilized with pride for the purpose of liberation. With the exception of gay men, no other group that has survived the camps has proudly claimed the identifier that denoted their demise. Yet, unlike any other persecuted group, the requests of gay men to be commemorated as the victims of Nazism has gone largely ignored (Heger, 1980, pp. 114-115; Rector, 1981, pp. 139-141). The feminist philosopher and Holocaust scholar, Joan Ringelheim, asks: "Can we so blithely reclaim and make right what has caused so much oppression without some careful scrutiny of our motives and politics?" She considers the use of words like "kike" and "faggot" to suggest that attempts at "reclamation" cannot be accomplished "without retaining some of the negativity that infests and infects the oppressor's use of the words" (Ringelheim, 1993, p. 386). Similarly, I claim that the "transformed" pink (or black) triangle cannot be altered through "reclamation." The down-turned triangles never really belonged to those marked by them in the way that "reclaiming" would suggest. Furthermore, in utilizing them as a symbol of pride one is implicitly promoting a denial of their horrific dimension. Consequently, wearing Nazi triangles may even be interpreted as a form of revisionism.

One cannot effectively eliminate oppression by mimicking the language, actions, and symbols of the oppressor. To best avoid the "valorization of the oppressor" (Ringelheim, 1993), we need our own spaces, language, and symbols if we are ever to claim a future that is markedly different from the past. In "repackaging" the cruel symbols of Nazism, we do not transcend the parameters established by them; rather we delude ourselves into thinking we have control-- we become complacent and perhaps complicitous in our own undoing.

------------ 1. Over the last few years I have often asked those wearing pink triangles to explain their meaning. Rarely have I received an accurate answer. Most reply only that the triangle symbolizes gay and lesbian pride. Moreover, with the exception of Holocaust survivors who I have heard object to its being worn, those outside of the gay and lesbian communities are even less familiar with the historical associations of the triangle. I strongly suspect that one of the appeals of this symbol is precisely its obscurity. That is, the pink triangle is a "discreet" signifier.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This article explores the politics of "reclamation." Its focus is on pink and black triangles, currently used as symbols for gay and lesbian pride and liberation. Previously, these same identifiers were worn by those destined for annihilation during the Holocaust. I suggest that, in [re]claiming these markers, activists, however well intentioned, run a path dangerously close to historical denial.

This article explores the politics of "reclamation." Its focus is on pink and black triangles, currently used as symbols for gay and lesbian pride and liberation. Previously, these same identifiers were worn by those destined for annihilation during the Holocaust. I suggest that, in [re]claiming these markers, activists, however well intentioned, run a path dangerously close to historical denial. This is not because historians dispute their victimization "but because most seem not to care" (Rector, 1981, p. 123). While the refusal to acknowledge Nazi tyranny against gay men is inexcusable, embracing the symbols of such persecution is likely to offer affirmation only among those ignorant of or careless with the past. Indeed, the adoption of such symbols might have the unintended consequence of concealing rather than promoting consciousness of the Holocaust. (1)

This is not because historians dispute their victimization "but because most seem not to care" (Rector, 1981, p. 123). While the refusal to acknowledge Nazi tyranny against gay men is inexcusable, embracing the symbols of such persecution is likely to offer affirmation only among those ignorant of or careless with the past. Indeed, the adoption of such symbols might have the unintended consequence of concealing rather than promoting consciousness of the Holocaust. (1) Why not, instead, adopt the symbols of life and love rather than sadism and destruction? Why has the rebellious color become pink and not lavender? Why not two male symbols or two women's symbols? The answer, in part, may be historical ignorance. It may also be internalized heterosexism; the willingness to embrace the very symbols of one's destruction reflects an incredible degree of hatred and self-contempt. In an age of AIDS and historical revisionism, it is frighteningly coincidental that the current identifiers are symbols from a period of death and totalitarianism. The triangles cannot be extricated from their use in concentration camps where, to quote one survivor, "love became corrupt excitement for the slaves and sadistic entertainment for the overseers" (Lengyel, 1993, p. 129).

Why not, instead, adopt the symbols of life and love rather than sadism and destruction? Why has the rebellious color become pink and not lavender? Why not two male symbols or two women's symbols? The answer, in part, may be historical ignorance. It may also be internalized heterosexism; the willingness to embrace the very symbols of one's destruction reflects an incredible degree of hatred and self-contempt. In an age of AIDS and historical revisionism, it is frighteningly coincidental that the current identifiers are symbols from a period of death and totalitarianism. The triangles cannot be extricated from their use in concentration camps where, to quote one survivor, "love became corrupt excitement for the slaves and sadistic entertainment for the overseers" (Lengyel, 1993, p. 129).